The sweetheart acquitted himself marvelously; and is satisfied to have broken his personal record with several minutes to spare. We went out to the sidewalk to cheer him as he dashed through our neighborhood, which made us feel connected to the marathon in a meaningful way without actually having to run. For this, we are grateful.

I'm also grateful to Jane for having arrived with gifts. Among them was a fantastic folio of fashion drawings by Erté, a man who was an idol to me growing up even though (especially because?) he was not supposed to have been. Young American males were not supposed to idolize fashion designers, we were supposed to idolize the various drug addicts, philanderers, dog fighters, and wife beaters who populate professional sports and popular music.

But I loved Erté, whose wild imagination and flowing line were so of-the-moment in the late teens and early twenties of the last century that they became emblematic of it. Erté was still actively cranking out work in the 1980s. By that time, of course, his style had become a caricature of itself; but the demand never flagged and he died (so I have read) with pen in hand, at work. I can only hope to face a similar fate.

The folio from Jane covers Erté's years as a fashion illustrator for Harper's Bazar (this was before they added the third "a" in "Bazaar"), 1918-1932. It's a book to fall into. This was the period during which the artist hit his stride for the first time, and you can sense him struggling to rein in his creativity. The sketches for Harper's were supposed to be practical–in the very broad sense that you could conceivably take one to your dressmaker and have her make a dress from the sketch–but some of them...

Well, I'll put it this way. There's one page titled, "Novel and Unusual Designs in Fur and Chiffon." Get the picture?

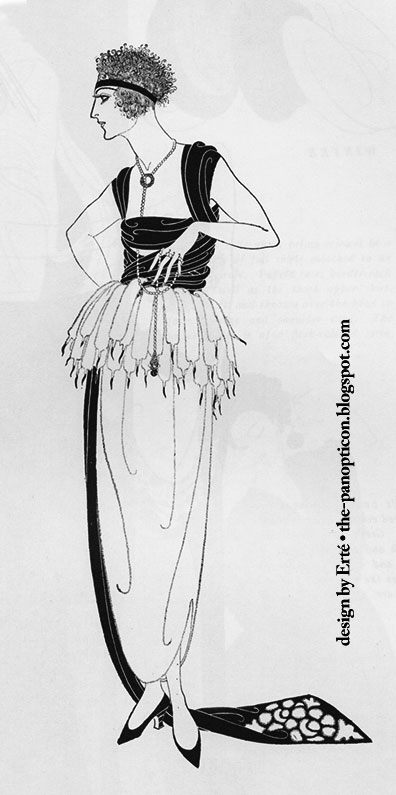

Here, I'll give you a picture.

This is an evening gown from December 1920.

The original caption read,

Erté wraps a long scarf of black satin about this lovely lady's shoulders and it forms the draped corsage, allowing one end to escape as a train. The skirt is of ermine.

Here's another, from March 1918.

This is described thus,

A suit of black satin that is easy of construction and very wearable is this Erté model. A cord, drawn through rings, makes a surplice closing and defines the waistline of the straight coat.

So, you know–practical. But not practical in the sense of, "What can I throw on to go down to the shops and pick up shoe polish and carrots?"

These are two of the more restrained designs.

But imagine my screaming joy–I mean it, I screamed–to find out as I pored over Jane's gift that along with "Novelties of Eastern Inspiration" and "Gowns Made to Do the Unexpected," Erté threw in designs for...

knitting bags.

Knitting bags.

And I do not mean bags that could contain knitting, I mean he intended them in no uncertain terms to carry around works in progress. They all appeared in 1918–the tail end of the first World War, when women of all stations were urged to knit their bit, so that may have had something to do with it.

Wanna see? Yeah, I bet you do. Here we go. (The captions, by the way, are the originals–verbatim.)

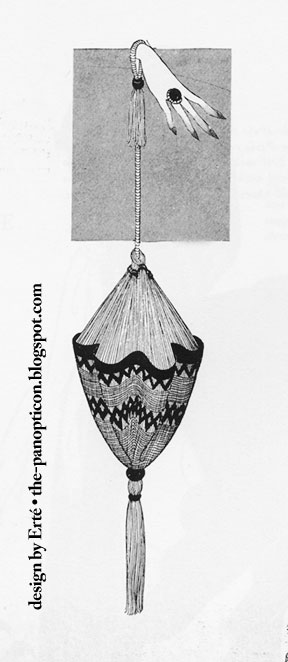

Design One, June 1918.

As knitting goes to every party, it is important that the bag that takes it be appropriate for the occasion. So with a summer frock, carry Erté's bag of silk tricot that is trimmed with straw.

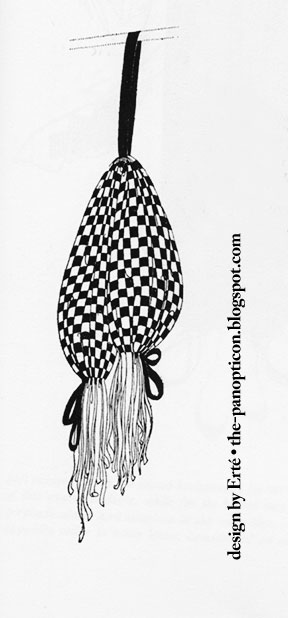

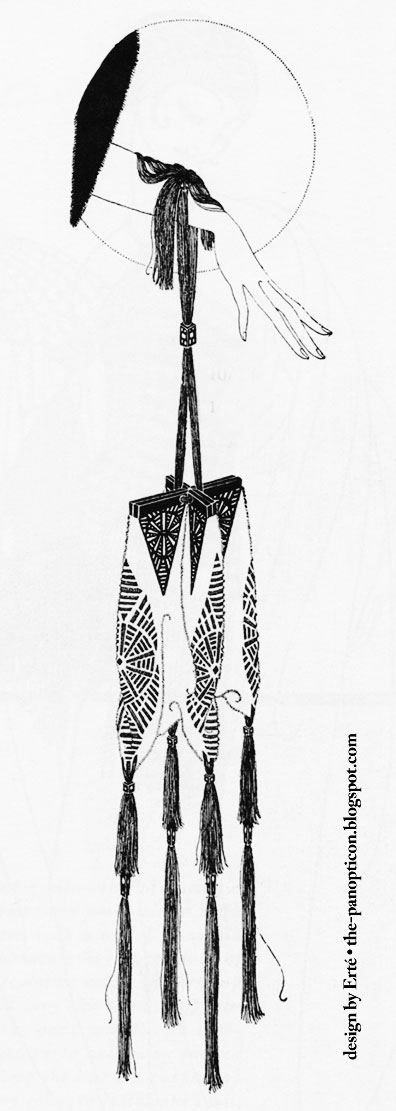

Design Two, May 1918.

Erté was indeed inspired when he laced black and white ribbons into a knitting-bag and then pulled one black ribbon to serve as a handle.

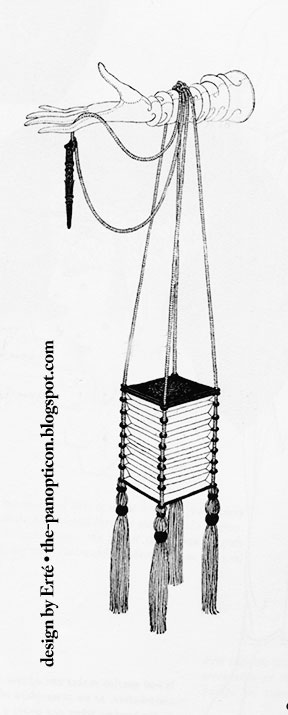

Design Three, May 1918.

Again he gives a practical suggestion in the lantern bag, for plaited silk is caught upon rings that slip up and down on silken cords and stretches like an accordion, making it equally simple to accommodate either a bulky sweater or diminutive wristlet.

Design Four, October 1918.

A sock will begin its life in luxurious surroundings when it is kept within a suede bag effectively embroidered with black silken threads and those of dull Indian red. The frame and beads are of ebony inlaid with ivory.

I didn't begin life in luxurious surroundings–but my socks might. Can somebody please rush these into production? Thanks ever so.